- Fossils

In Death Valley National Park: A site dedicated to the paleontology,

geology, and natural wonders of Death Valley National Park; lots

of on-site photographs of scenic localities within the park;

images of fossils specimens; links to many virtual field trips

of fossil-bearing interest.

- Fossil

Insects And Vertebrates On The Mojave Desert, California:

Journey to two world-famous fossil sites in the middle Miocene

Barstow Formation: one locality yields upwards of 50 species

of fully three-dimensional, silicified freshwater insects, arachnids,

and crustaceans that can be dissolved free and intact from calcareous

concretions; a second Barstow Formation district provides vertebrate

paleontologists with one of the greatest concentrations of Miocene

mammal fossils yet recovered from North America--it's the type

locality for the Bartovian State of the Miocene Epoch, 15.9 to

12.5 million years ago, with which all geologically time-equivalent

rocks in North American are compared.

- A

Visit To Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada:

Take a virtual field trip to a Nevada locality that yields the

most complete, diverse, fossil assemblage of terrestrial Miocene

plants and animals known from North America--and perhaps the

world, as well. Yields insects, leaves, seeds, conifer needles

and twigs, flowering structures, pollens, petrified wood, diatoms,

algal bodies, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, bird feathers, fish,

gastropods, pelecypods (bivalves), and ostracods.

- Fossils

At Red Rock Canyon State Park, California: Visit wildly

colorful Red Rock Canyon State Park on California's northern

Mojave Desert, approximately 130 miles north of Los Angeles--scene

of innumerable Hollywood film productions and commercials over

the years--where the Middle to Late Miocene (13 to 7 million

years old) Dove Spring Formation, along with a classic deposit

of petrified woods, yields one of the great terrestrial, land-deposited

Miocene vertebrate fossil faunas in all the western United States.

- Cambrian

And Ordovician Fossils At Extinction Canyon, Nevada:

Visit a site in Nevada's Great Basin Desert that yields locally

common whole and mostly complete early Cambrian trilobites, in

addition to other extinct organisms such as graptolites (early

hemichordate), salterella (small conical critter placed in the

phylum Agmata), Lidaconus (diminutive tusk-shaped shell of unestablished

zoological affinity), Girvanella (photosynthesizing cyanobacterial

algae), and Caryocaris (a bivalved crustacean).

- Late

Pennsylvanian Fossils In Kansas: Travel to the midwestern

plains to discover the classic late Pennsylvanian fossil wealth

of Kansas--abundant, supremely well-preserved associations of

such invertebrate animals as brachiopods, bryozoans, corals,

echinoderms, fusulinids, mollusks (gastropods, pelecypods, cephalopods,

scaphopods), and sponges; one of the great places on the planet

to find fossils some 307 to 299 million years old.

- Fossil

Plants Of The Ione Basin, California: Head to Amador

County in the western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada

to explore the fossil leaf-bearing Middle Eocene Ione Formation

of the Ione Basin. This is a completely undescribed fossil flora

from a geologically fascinating district that produces not only

paleobotanically invaluable suites of fossil leaves, but also

world-renowned commercial deposits of silica sand, high-grade

kaolinite clay and the extraordinarily rare Montan Wax-rich lignites

(a type of low grade coal).

- Ice

Age Fossils At Santa Barbara, California--Journey

to the famed So Cal coastal community of Santa Barbara (about

a 100 miles north of Los Angeles) to explore one of the best

marine Pleistocene invertebrate fossil-bearing areas on the west

coast of the United States; that's where the middle Pleistocene

Santa Barbara Formation yields nearly 400 species of pelecypod

bivalve mollusks, gastropods, chitons, scaphopods, pteropods,

brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, ostracods (minute bivalve crustaceans),

worm tubes, and foraminifers.

- Trilobites

In The Marble Mountains, Mojave Desert, California:

Take a trip to the place that first inspired my life-long fascination

and interest in fossils--the classic trilobite quarry in the

Lower Cambrian Latham Shale, in the Marble Mountains of California's

Mojave Desert. It's a special place, now included in the rather

recently established Trilobite Wilderness, where some 21 species

of ancient plants and animals have been found--including trilobites,

an echinoderm, a coelenterate, mollusks, blue-green algae and

brachiopods.

- Fossil

Plants In The Neighborhood Of Reno, Nevada: Visit

two famous fossil plant localities in the Great Basin Desert

near Reno, Nevada--a place to find leaves, seeds, needles, foilage,

and cones in the middle Miocene Pyramid and Chloropagus Formations,

15.6 and 14.8 to 13.3 million years old, respectively.

- Early

Cambrian Fossils Of Westgard Pass, California: Visit

the Westgard Pass area, a world-renowned geologic wonderland

several miles east of Big Pine, California, in the neighboring

White-Inyo Mountains, to examine one of the best places in the

world to find archaeocyathids--an enigmatic invertebrate animal

that went extinct some 510 million years ago, never surviving

past the early Cambrian; also present there in rocks over a half

billion years old are locally common trilobites, plus annelid

and arthropod trails, and early echinoderms.

- Plant

Fossils At The La Porte Hydraulic Gold Mine, California:

Journey to a long-abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the neighborhood

of La Porte, northern Sierra Nevada, California, to explore the

upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, which yields some 43 species of Cenozoic

plants, mainly a bounty of beautifully preserved leaves 34.2

million years old.

- A

Visit To Ammonite Canyon, Nevada: Explore one of the

best-exposed, most complete fossiliferous marine late Triassic

through early Jurassic geologic sections in the world--a place

where the important end-time Triassic mass extinction has been

preserved in the paleontological record. Lots of key species

of ammonites, brachiopods, corals, gastropods and pelecypods.

- Fossil

Plants At The Chalk Bluff Hydraulic Gold Mine, California:

Take a field trip to the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western

foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, for leaves, seeds, flowering

structures, and petrified wood from some 70 species of middle

Eocene plants.

- Field

Trip To The Alexander Hills Fossil District, Mojave Desert, California:

Visit a locality outside the southern sector of Death Valley

National Park to explore a paleontological wonderland that produces:

Precambrian stromatolites over a billion years old; early skeletonized

eukaryotic cells of testate amoebae over three-quarters of billion

years old; early Cambrian trilobites, archaeocyathids, annelid

trails, arthropod tracks, and echinoderm material; Pliocene-Pleistocene

vertebrate and invertebrate faunas; and late middle Miocene camel

tracks, petrified palm wood, petrified dicotlyedon wood, and

permineralized grasses.

- Late

Triassic Ichthyosaur And Invertebrate Fossils In Nevada:

Journey to two classic, world-famous fossil localities in the

Upper Triassic Luning Formation of Nevada--Berlin-Ichthyosaur

State Park and Coral Reef Canyon. At Berlin-Ichthyosaur, observe

in-situ the remains of several gigantic ichthyosaur skeletons

preserved in a fossil quarry; then head out into the hills, outside

the state park, to find plentiful pelecypods, gastropods, brachiopods

and ammonoids. At Coral Reef Canyon, find an amazing abundance

of corals, sponges, brachiopods, echinoids (sea urchins), pelecypods,

gastropods, belemnites and ammonoids.

- Fossils

In Millard County, Utah: Take virtual field trips

to two world-famous fossil localities in Millard County, Utah--Wheeler

Amphitheater in the trilobite-bearing middle Cambrian Wheeler

Shale; and Fossil Mountain in the brachiopod-ostracod-gastropod-echinoderm-trilobite

rich lower Ordovician Pogonip Group.

- Fossil

Plants, Insects And Frogs In The Vicinity Of Virginia City, Nevada:

Journey to a western Nevada badlands district near Virginia City

and the Comstock Lode to discover a bonanza of paleontology in

the late middle Miocene Coal Valley Formation.

- Paleozoic

Era Fossils At Mazourka Canyon, Inyo County, California:

Visit a productive Paleozoic Era fossil-bearing area near Independence,

California--along the east side of California's Owens Valley,

with the great Sierra Nevada as a dramatic backdrop--a paleontologically

fascinating place that yields a great assortment of invertebrate

animals.

- Fossils

From The Kettleman Hills, California: Visit one of

California's premiere Pliocene-age (approximately 4.5 to 2.0

million years old) fossil localities--the Kettleman Hills, which

lie along the western edge of California's Great Central Valley

northwest of Bakersfield. This is where innumerable sand dollars,

pectens, oysters, gastropods, "bulbous fish growths"

and pelecypods occur in the Etchegoin, San Joaquin and Tulare

Formations.

- Field

Trip To The Kettleman Hills Fossil District, California:

Take a virtual field trip to a classic

site on the western side of California's Great Central Valley,

roughly 80 miles northwest of Bakersfield, where several Pliocene-age

(roughly 4.5 to 2 million years old) geologic rock formations

yield a wealth of diverse, abundant fossil material--sand dollars,

scallop shells, oysters, gastropods and "bulbous fish growths"

(fossil bony tumors--found nowhere else, save the Kettleman Hills),

among many other paleontological remains.

- A

Visit To The Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed, Southern California:

Travel to the dusty hills near Bakersfield, California, along

the eastern side of the Great Central Valley in the western foothills

of the Sierra Nevada, to explore the world-famous Sharktooth

Hill Bone Bed, a Middle Miocene marine deposit some 16 to 15

million years old that yields over a hundred species of sharks,

rays, bony fishes, and sea mammals from a geologic rock formation

called the Round Mountain Silt Member of the Temblor Formation;

this is the most prolific marine, vertebrate fossil-bearing Middle

Miocene deposit in the world.

- High

Sierra Nevada Fossil Plants, Alpine County, California:

Visit a remote fossil leaf and petrified wood locality in the

Sierra Nevada, at an altitude over 8,600 feet, slightly above

the local timberline, to find 7 million year-old specimens of

cypress, Douglas-fir, White fir, evergreen live oak, and giant

sequoia, among others.

- In

Search Of Fossils In The Tin Mountain Limestone, California:

Journey to the Death Valley area of Inyo County, California,

to explore the highly fossiliferous Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain

Limestone; visit three localities that provide easy access to

a roughly 358 million year-old calcium carbate accumulation that

contains well preserved corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids,

and ostracods--among other major groups of invertebrate animals.

- Middle

Triassic Ammonoids From Nevada: Travel to a world-famous

fossil locality in the Great Basin Desert of Nevada, a specific

place that yields some 41 species of ammonoids, in addition to

five species of pelecypods and four varieties of belemnites from

the Middle Triassic Prida Formation, which is roughly 235 million

years old; many paleontologists consider this specific site the

single best Middle Triassic, late Anisian Stage ammonoid locality

in the world. All told, the Prida Formation yields 68 species

of ammonoids spanning the entire Middle Triassic age, or roughly

241 to 227 million years ago.

- Late

Miocene Fossil Leaves At Verdi, Washoe County, Nevada:

Explore a fascinating fossil leaf locality not far from Reno,

Nevada; find 18 species of plants that prove that 5.8 million

years ago this part of the western Great Basin Desert would have

resembled, floristically, California's lush green Gold Country,

from Placerville south to Jackson.

- Fossils

Along The Loneliest Road In America: Investigate the

extraordinary fossil wealth along some 230 miles of The Loneliest

Road In America--US Highway 50 from the vicinity of Eureka, Nevada,

to Delta in Millard County, Utah. Includes on-site images and

photographs of representative fossils (with detailed explanatory

text captions) from every geologic rock deposit I have personally

explored in the neighborhood of that stretch of Great Basin asphalt.

The paleontologic material ranges in geologic age from the middle

Eocene (about 48 million years ago) to middle Cambrian (approximately

505 million years old).

- Fossil

Bones In The Coso Range, Inyo County, California:

Visit the Coso Range Wilderness, west of

Death Valley National Park at the southern end of California's

Owens Valley, where vertebrate fossils some 4.8 to 3.0 million

years old can be observed in the Pliocene-age

Coso Formation: It's a paleontologically significant place that

yields many species of mammals, including the remains of Equus

simplicidens, the Hagerman Horse, named for its spectacular

occurrences at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

in Idaho; Equus simplicidens is

considered the earliest known member of the genus Equus, which

includes the modern horse and all other equids.

- Field

Trip To A Vertebrate Fossil Locality In The Coso Range, California: Take a cyber-visit to the famous bone-bearing

Pliocene Coso Formation, Coso Mountains, Inyo County, California;

includes detailed text for the field trip, plus on-site images

and photographs of vertebrate fossils.

- Fossil

Plants At Aldrich Hill, Western Nevada: Take

a field trip to western Nevada, in the vicinity of Yerington,

to famous Aldrich Hill, where one can collect some 35 species

of ancient plants--leaves, seeds and twigs--from the Middle Miocene

Aldirch Station Formation, roughly 12 to 13 million years old.

Find the leaves of evergreen live oak, willow, and Catalina Ironwood

(which today is restricted in its natural habitat solely to the

Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California), among

others, plus the seeds of many kinds of conifers, including spruce;

expect to find the twigs of Giant Sequoias, too.

- Fossils

From Pleistocene Lake Manix, California: Explore the

badlands of the Manix Lake Beds on California's Mojave Desert,

an Upper Pleistocene deposit that produces abundant fossil remains

from the silts and sands left behind by a great fresh water lake,

roughly 350,000 to 19,000 years old--the Manix Beds yield many

species of fresh water mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods),

skeletal elements from fish (the Tui Mojave Chub and Three-Spine

Stickleback), plus roughly 50 species of mammals and birds, many

of which can also be found in the incredible, world-famous La

Brea Tar Pits of Los Angeles.

- Field

Trip To Pleistocene Lake Manix, California: Go on

a virtual field trip to the classic, fossiliferous badlands carved

in the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation, Mojave Desert, California.

It's a special place that yields beaucoup fossil remains, including

fresh water mollusks, fish (the Mojave Tui Chub), birds and mammals.

- Trilobites

In The Nopah Range, Inyo County, California: Travel to a locality well outside the boundaries

of Death Valley National Park to collect trilobites in the Lower

Cambrian Pyramid Shale Member of the Carrara Formation.

- Ammonoids

At Union Wash, California: Explore

ammonoid-rich Union Wash near Lone Pine, California, in the shadows

of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United

States. Union Wash is a ne plus ultra place to find Early Triassic

ammonoids in California. The extinct cephalopods occur in abundance

in the Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, with the dramatic

back-drop of the glacier-gouged Sierra Nevada skyline in view

to the immediate west.

- A

Visit To The Fossil Beds At Union Wash, Inyo County California:

A virtual field trip to the fabulous ammonoid

accumulations in the Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, Inyo

County, California--situated in the shadows of Mount Whitney,

the highest point in the contiguous United States.

- Ordovician

Fossils At The Great Beatty Mudmound, Nevada: Visit a classic 475-million-year-old fossil

locality in the vicinity of Beatty, Nevada, only a few miles

east of Death Valley National Park; here, the fossils occur in

the Middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone at a prominent

Mudmound/Biohern. Lots of fossils can be found there, including

silicified brachiopods, trilobites, nautiloids, echinoderms,

bryozoans, ostracodes and conodonts.

- Paleobotanical

Field Trip To The Sailor Flat Hydraulic Gold Mine, California:

Journey on a day of paleobotanical discovery with the FarWest

Science Foundation to the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--to

famous Sailor Flat, an abandoned hydraulic gold mine of the mid

to late 1800s, where members of the foundation collect fossil

leaves from the "chocolate" shales of the Middle Eocene

auriferous gravels; all significant specimens go to the archival

paleobotanical collections at the University California Museum

Of Paleontology in Berkeley.

- Early

Cambrian Fossils In Western Nevada: Explore

a 518-million-year-old fossil locality several miles north of

Death Valley National Park, in Esmeralda County, Nevada, where

the Lower Cambrian Harkless Formation yields the largest single

assemblage of Early Cambrian trilobites yet described from a

specific fossil locality in North America; the locality also

yields archeocyathids (an extinct sponge), plus salterella (the

"ice-cream cone fossil"--an extinct conical animal

placed into its own unique phylum, called Agmata), brachiopods

and invertebrate tracks and trails.

- Fossil

Leaves And Seeds In West-Central Nevada: Take

a field trip to the Middlegate Hills area in west-central Nevada.

It's a place where the Middle Miocene Middlegate Formation provides

paleobotany enthusiasts with some 64 species of fossil plant

remains, including the leaves of evergreen live oak, tanbark

oak, bigleaf maple, and paper birch--plus the twigs of giant

sequoias and the winged seeds from a spruce.

- Ordovician

Fossils In The Toquima Range, Nevada: Explore

the Toquima Range in central Nevada--a locality that yields abundant

graptolites in the Lower to Middle Ordovician Vinini Formation,

plus a diverse fauna of brachiopods, sponges, bryozoans, echinoderms

and ostracodes from the Middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone.

- Fossil

Plants In The Dead Camel Range, Nevada: Visit

a remote site in the vicinity of Fallon, Nevada, where the Middle

Miocene Desert Peak Formation provides paleobotany enthusiasts

with 22 species of nicely preserved leaves from a variety

of deciduous trees and evergreen live oaks, in addition to samaras

(winged seeds), needles and twigs from several types of conifers.

- Early

Triassic Ammonoid Fossils In Nevada: Visit the two

remote localities in Nevada that yield abundant, well-preserved

ammonoids in the Lower Triassic Thaynes Formation, some 240 million

years old--one of the sites just happens to be the single finest

Early Triassic ammonoid locality in North America.

- Fossil

Plants At Buffalo Canyon, Nevada: Explore the wilds

of west-central Nevada, a number of miles from Fallon, where

the Middle Miocene Buffalo Canyon Formation yields to seekers

of paleontology some 54 species of deciduous and coniferous varieties

of 15-million-year-old leaves, seeds and twigs from such varieties

as spruce, fir, pine, ash, maple, zelkova, willow and evergreen

live oak

- High

Inyo Mountains Fossils, California: Take a ride to

the crest of the High Inyo Mountains to find abundant ammonoids

and pelecypods--plus, some shark teeth and terrestrial plants

in the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, roughly 325 million

years old.

- Field

Trip To The Copper Basin Fossil Flora, Nevada: Visit

a remote region in Nevada, where the Late Eocene Dead Horse Tuff

provides seekers of paleobotany with some 42 species of ancient

plants, roughly 39 to 40 million years old, including the leaves

of alder, tanbark oak, Oregon grape and sassafras.

- Fossil

Plants And Insects At Bull Run, Nevada: Head

into the deep backcountry of Nevada to collect fossils from the

famous Late Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, which yields, in

addition to abundant fossil fly larvae, a paleobotanically wonderful

association of winged seeds and fascicles (bundles of

needles) from many species of conifers, including fir, pine,

spruce, larch, hemlock and cypress. The plants are some 37 million

old and represent an essentially pure montane conifer forest,

one of the very few such fossil occurrences in the Tertiary Period

of the United States.

- A

Visit To The Early Cambrian Waucoba Spring Geologic Section,

California: Journey to the northwestern sector of

Death Valley National Park to explore the classic, world-famous

Waucoba Spring Early Cambrian geologic section, first described

by the pioneering paleontologist C.D. Walcott in the late 1800s;

surprisingly well preserved 540-510 million-year-old remains

of trilobites, invertebrate tracks and trails, Girvanella

algal oncolites and archeocyathids (an extinct variety of

sponge) can be observed in situ.

- Petrified

Wood From The Shinarump Conglomerate: An image of

a chunk of petrified wood I collected from the Upper Triassic

Shinarump Conglomerate, outside of Dinosaur National Monument,

Colorado.

- Fossil

Giant Sequoia Foliage From Nevada: Images of the youngest

fossil foliage from a giant sequoia ever discovered in the geologic

record--the specimen is Lower Pliocene in geologic age, around

5 million years old.

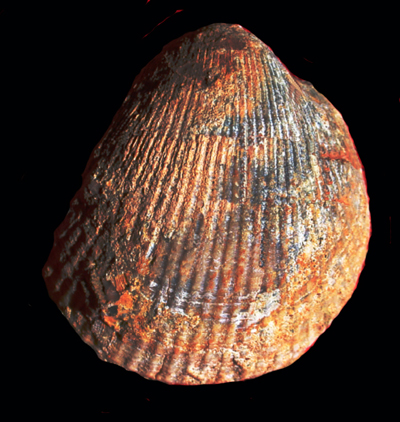

- Some

Favorite Fossil Brachiopods Of Mine: Images of several

fossil brachiopods I have collected over the years from Paleozoic,

Mesozoic and Cenozoic-age rocks.

- For information on what can and cannot be collected legally

from America's Public Lands, take a look at Fossils

On America's Public Lands and Collecting

On Public Lands--brochures that the Bureau Of Land Management

has allowed me to transcribe.

- In

Search Of Vanished Ages--Field Trips To Fossil Localities In

California, Nevada, And Utah--My fossils-related field

trips in full print book form (pdf). 98,703 words (equivalent

to a medium-size hard cover work of non-fiction); 250 printed

pages (equivalent to about 380 pages in hard cover book form);

27 chapters; 30 individual field trips to places of paleontological

interest; 60 photographs--representative on-site images and pictures

of fossils from each locality visited.

United

States Geological Survey Papers (Public Domain)

Online versions

of USGS publications

|