|

Relatively few localities on Earth record the important

Precambrian-Early Cambrian transition period--a fascinating and

truly mysterious interval some 550 to 509 million years ago,

when abundant animal life with a hard external covering first

appears in the geologic record.

One of the best places to study this crucial boundary between

two major geological Eras (Precambrian and Paleozoic) is the

Waucoba Spring district some 35 miles southeast of Big Pine,

California, on the eastern slopes of the Inyo Mountains, a locality

that now lies within the northwestern border of Death Valley

National Park (as of 1994, when the Desert Protection Act became

law). Here can be found the classic Waucoba Spring geologic

section, first measured and described by legendary Cambrian specialist

Charles Doolittle Walcott in the 1890s.

Walcott is of course most famous for discovering the Middle

Cambrian Burgess Shale fauna of Canada, an extraordinary assemblage

of soft-bodied organisms also recognized from a specific Early

Cambrian site in China. But Walcott was vitally interested in

all aspects of the Cambrian Period, and his detailed analysis

of the Waucoba Spring geologic section elevated the site to the

status of type reference section for the Waucoban Series of the

lowermost Cambrian (542 to 509 million years ago). This means

that all age-equivalent strata in the world are correlated with

the Waucoba Spring rocks.

Not only is the important Precambrian-Cambrian boundary

well exposed near Waucoba Spring, but the sequence is amazingly

fossiliferous for strata of such profound antiquity. Among the

diverse fossil types that can be observed in situ at Waucoba

are archeocyathids, an extinct invertebrate animal that secreted

a conical to cup-shaped shell typically one-quarter to two inches

long--among the earliest reef-forming animals on Earth, it was

likely an early calcareous sponge, although not a few archeocyathid

purists still prefer to call it a unique organism with no known

modern analogs, deserving of its own scientific Phylum. There

are also worm trails, miscellaneous invertebrate tracks and trails

(probably from annelids and trilobitic arthropods), salterella

(an early experiment, now an extinct member of the Phylum called

Agmata, with a small tusk-shaped shell roughly a quarter inch

long), algal bodies, brachiopods, and trilobites. Most of the

fossil material is surprisingly well-preserved, and there is

even one specific site where perfect, intact trilobite carapaces

can be observed. Please note of course that the Waucoba Spring

geologic section presently resides within the borders of Death

Valley National Park. One must not remove fossil specimens within

the park's boundaries without formal, written approval from the

National Park Service personnel at Furnace Creek in Death Valley.

To reach the Waucoba Spring geologic section, first travel

to the intersection of Highway 395 and State Route 168 in Big

Pine, Owens Valley, California. Turn east on route 168 and proceed

2.4 miles to Death Valley Road (to Saline Valley, Eureka Valley,

and Scotty's Castle). Turn right here.

At the 2.3 mile mark from the SR 168, look to the north

of the road (left) and you will begin to see impressive badlands

carved in sedimentary rocks deposited in ancient Lake Waucoba--a

dominantly detrital sequence of calcareous silts and sands and

water-laid volcanic tuffs that accumulated 2.63 to 2.06 million

years ago during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene.

In the 1890s, C.D. Walcott, on his way to the Early Cambrian

rocks exposed farther southeast, discovered an abundance of freshwater

snail fossils from several beds in the Plio-Pleistocene section.

For those interested in researching the original reference to

the molluscan assemblage, Walcott's paper appears in the Journal

of Geology, volume 5, 1897. In 2012, a scientific examination

of the Waucoba Lake Beds--their formal geologic name (though

some folks prefer "Waucobi Lake Beds")--disclosed numerous

species of ostracods (a minute bi-valved crustacean), as well.

When you have driven 13.5 miles from the SR 168, turn right

on Waucoba-Saline Road. This path can be followed all the way

through Saline Valley, just inside the westernmost boundary of

Death Valley National Park. It is for the most part a well-graded

dirt road, although the Whippoorwill Canyon area a few miles

up ahead tends to be rocky and rutted--a condition one would

expect to encounter on a dirt route through such a defile in

the mountains.

At the 8.1 mile point from Death Valley Road, Waucoba-Saline

Road begins to cut through one of the oldest recognizable sedimentary

rock formations in North America: the Wyman Formation. The dark-brown

to gray-brown exposures along either side of the path consist

of heat and pressure-altered sandstones and siltstones. Some

portions of the formation have been changed to quartzite through

the eons of tortuous metamorphism. From a distance, these Wyman

rocks have a suspicious volcanic aspect: a blocky, basalt-like

tone and style of outcropping. Closer examination, though, reveals

the obvious sedimentary nature of the material; the strata reveal

the characteristic layered bedding and fine-grained composition

of altered sandstones and siltstones.

No animal remains have been recovered from the Wyman Formation.

At this point in the local stratigraphic section you are standing

thousands of feet below the first occurrence of olenellid trilobites,

which in a traditional sense used to define the beginning of

the Cambrian Period and the Paleozoic Era. Not any longer, though.

The Precambrian-Cambrian boundary is now defined as either (1)

the appearance of a trace fossil called Treptichnus pedum

(feeding trails of a supposed annelid), or (2) a distinctive

negative carbon isotope excursion in the sediments at the boundary.

Rarely do the two defining occurrences--biological and geochemical--occur

together, but there's one place in Death Valley National Park

where such a unique combination of defining events can be studied.

It's in Boundary Canyon near Daylight Pass, along the road to

Beatty, Nevada, in the lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation.

Unicellular organisms and algae most certainly lived here

during Wyman time--nearly a billion or so years ago--but due

to intense metamorphism any trace of their former existence has

long since been obliterated. Still and all, a relatively

few pure limestone pods have been reported in the Wyman. If such

rocks could be located in the predominantly detrital terrigenous

terrain, one would naturally expect a greater opportunity to

discover some of the oldest identifiable animal fossils on Earth.

At a point 13.8 miles from Death Valley Road, the path

starts to slice through scenic Whippoorwill Canyon. Rocks exposed

here belong to the upper Precambrian Reed Dolomite and the Upper

Precambrian-Lower Cambrian Deep Spring Formation, roughly 560

to 542 million years old. In contrast to the predominantly detrital

Wyman Formation, these two rock units contain relatively high

percentages of carbonates, rocks composed of calcium carbonate

and magnesium carbonate (dolomite) precipitated on the floors

of vast shallow seas.

Near the very top of the Reed Dolomite, in strata transitional

with the younger Deep Spring Formation, scientists have found

one of the earliest evidences of a widespread variety of animals

with shells. Most of the described specimens are minute, measured

in millimeters (about one-twenty-fourth of an inch). But they

represent such identifiable forms as worm tubes and primitive

mollusks. I have personally scoured the Whippoorwill Canyon area

for fossils but have yet to find any there. The worm-tube/primitive

mollusk horizon occurs in the same formations at Mount Dunfey

in neighboring Esmeralda County, Nevada. It also shows up in

the Westgard Pass region several miles east of Big Pine. Even

so, this is an excellent place for paleontological explorations.

It is one of the most significant geologic regions in all the

world. Because most of the sedimentary material exposed here

is miraculously unaltered, there is great potential for the discovery

of the oldest identifiable animal with a shell.

An aside here. Another ultra-significant Precambrian-Cambrian

transitional stratigraphic section can be studied in the Alexander

Hills District, southeast of Death Valley National Park,

a California Mojave Desert locality that produces: Precambrian

stromatolites over a billion years old; early skeletonized eukaryotic

cells of testate amoebae around three-quarters of a billion years

old; and early Cambrian trilobites, archaeocyathids, annelid

trails, arthropod tracks, and echinoderm material.

For two miles the Waucoba-Saline Road carves through the

Precambrian strata of Whippoorwill Canyon. All along this route

you move gradually upsection--that is, as you proceed south the

rocks become progressively younger in geologic age. The base,

or the section bearing the oldest layers of the classic Waucoban

Spring section, as defined by pioneering paleontologist Walcott,

occurs in transitional rocks of the Late Precambrian-Lower Cambrian

Deep Spring Formation and the overlying lowermost Cambrian Campito

Formation. This world-famous change from the Precambrian to the

Paleozoic Era lies directly to the east of the Waucoba-Saline

Road, 16 miles from the Death Valley Road junction. To the left

of the road you will note typically blocky weathering black to

brownish quartzites and shales of the Andrews Mountain member

of the Campito Formation, within which some of the oldest olenellid

trilobites have been recovered. The fossils are by no means

common here--they are, indeed, frustratingly rare: one lone occurrence

discovered by a very lucky paleontologist, although unfortunate

evidence exists to conclude that perhaps that specimen came from

much younger strata; the trilobite was recovered from a wash

and could have been transported to the site of discovery. Outcrops

of the Andrews Mountain member in neighboring Esmeralda County

have yielded a few identifiable trilobite specimens.

After examining the exposures of the Campito Formation

here, proceed one additional mile to the turnoff to Waucoba Spring,

where you will be within a short hiking distance of fossiliferous

Early Cambrian strata in the Waucoba Spring geologic section.

Waucoba Spring lies approximately one-half mile west of Waucoba-Saline

Road, 17 miles south of the intersection with Death Valley Road.

The spring is an old and famous watering hole for the local

fauna, including feral burros whose presence in the Death Valley

region has generated much controversy. Some investigators claim

the burros foul critical watering holes and scare off more sensitive

creatures such as bighorn sheep. Others exonerate the asses,

pointing out that they have just as much right to exist in the

wild as any indigenous creature and charges that they are solely

to blame for the ruination of the ecology are absurd.

During my first visit to the Waucoba a number of years

ago, I recall having observed quite a few burros. They'd halt

right in front of a moving vehicle, staring inscrutably ahead.

Subsequent trips to the Waucoban wilds disclosed a dramatic drop

in the observable burro population. I do not know whether natural

selection has been weeding out the weak or artificial measures

have been employed--such as periodic thinning of the paces/herds

by gunfire.

Excellent representative exposures of the classic Early

Cambrian Waucoba Spring section described by Walcott lie to the

east of Waucoba-Saline Valley Road. To reach the fossil-bearing

exposures it is necessary to hike approximately a quarter of

a mile to the nearest hillslope, directly east of the turnoff

to Waucoba Spring. This slope is composed of the greenish shales

and quartzites of the Montenegro Member of the Campito Formation,

within whose detrital rocks can be seen worm trails, invertebrate

tracks (many made by trilobites, but also several types that

have not yet been positively identified) and trilobite head shields,

or cephalons (complete specimens rather rare). Another region

in which to hunt for the oldest reasonably common trilobites

in the geologic record is over in neighboring Esmeralda County,

Nevada, where several Montenegro Member sections yield many complete

Fallotaspis trilobites, along with several other early

spectacularly preserved olenellid trilobites.

As you continue to hike in a generally southeasterly direction

along the hillside, the greenish shales and quartzites give way

to geologically younger gray-blue to buff-brown archaeocyathid-bearing

limestones of the Poleta Formation. Most of the extinct calcareous

sponges range from a half-inch to two inches in length, and quite

a number of archeocyathid fragments have weathered out of the

rocks. A few of the more densely packed clusters of archeocyathids

observed in the limestones are likely the preserved remains of

primitive, localized reefs.

All of the trilobites within the Poleta Formation occur

in the younger, gray-green shales which lie directly on top of

the archeocyathid-bearing limestone. In addition to the trilobites,

perfect specimens of which remain elusively infrequent in the

extensive deposits of shale, abundant worm trails and invertebrate

tracks can also be seen. These fossiliferous shales are in striking

stratigraphic contact with the older archeocyathid limestone,

and the lithologic contrast is so distinctive that it can be

traced with assurance throughout the Waucoba Spring district

and western Great Basin, in general (northern Inyo County and

western Esmeralda County, Nevada).

Additional superior fossil material can be observed in

place from the next-youngest geologic rock unit in the Waucoban

section, the Harkless Formation. Abundant worm trails and invertebrate

tracks, salterella (diminutive tube-like, roughly conical shells

secreted by an extinct animal of unestablished zoological affinity),

and a few species of archeocyathids are characteristic of the

formation, which outcrops roughly three-quarters of a mile to

one mile directly east of the Waucoba Spring turnoff. The Harkless

is chiefly a terrigenous unit of gray shale and siltstone, interbedded

with brownish quartzites. Minor lenticular blue-gray limestones

in the youngest phases of deposition often yield large archeocyathids,

some up to nine inches in length.

Expect to conduct extended periods of hiking in order to

examine all of the fossil material present in the Waucoba geologic

section directly east of the turnoff to Waucoba Spring. The trilobites

in particular are seldom even common at any one locality. They

are usually confined to the greenish shales of the Poleta Formation,

several feet above the archeocyathid-rich limestones.

A better place in which to observe in situ trilobites lies

farther south, in much younger exposures of the Early Cambrian

Waucoba Spring geologic section at Algae Ridge, where the Lower

Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone contains abundant fossil remains

of a species of cyanobacterial blue-green algae called Girvanella.

The Mule Spring limestone contains the highest concentration

of fossil algae of any Cambrian formation in the Great Basin.

It is estimated that in some horizons Girvanella algal

bodies constitute fully 40 percent of the limestones by volume.

At Algae Ridge these fossil remains are certainly locally prolific,

appearing in the blue-gray rocks as oval to circular black concretionary

structures roughly one-quarter to three-quarters of an inch in

diameter.

The Mule Spring Limestone marks the very top, or youngest

part of the Waucoba Spring geologic reference section. Above

it lies the Middle Cambrian Monola Formation whose prominent

exposures can be seen about a mile and a half to the south, near

where the dramatic expanse of Saline Valley commences.

The prime trilobite locality lies on Algae Ridge in the

Saline Valley Formation. Prior to December 1994 this site was

open to hobby fossil collecting, lying as it did outside the

boundaries of Death Valley National Monument. Please note that

it now lies within the borders of Death Valley National Park.

Look and touch, but don't keep anything you find there--unless

it's a photograph of a fossil specimen, of course.

At the fossil site one can examine abundant trilobite head

shields, plus occasional perfect, intact specimens. During my

last visit to the site before it was assimilated by the national

park system, I was fortunate to find three complete, whole trilobites--a

powerfully exhilarating and rewarding experience, to be certain.

Perfect specimens were surprisingly common, interestingly enough--a

fact that helped set this specific Early Cambrian fossil site

apart from most others.

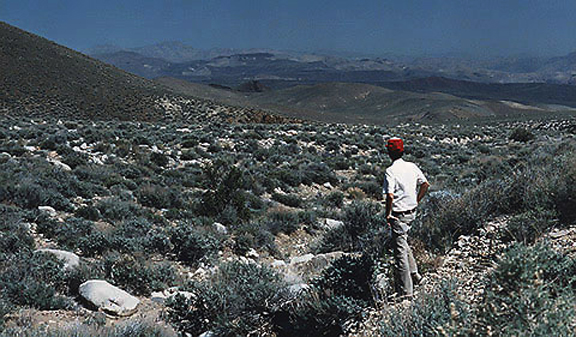

The Waucoba Spring district is a rugged and pristine land.

It is also out in the middle of nowhere, miles from civilization.

This means that adventurers traveling to the region must make

certain that their vehicles are in perfect working condition

and carry with them extra food, plenty of water, spare fan belts

(and know how to change one!) and protective clothing. In short,

take all necessary precautions to ensure a safe experience.

Most of my Waucoba Spring trips were during the early Spring,

mainly in early to mid April. I'm not presuming to suggest that

this is the most comfortable time of the year there, but by way

personal experience I recall one August spell that turned into

pure vapor lock of the brain--soaring daytime temperatures even

up in Whippoorwill Canyon at elevations over 7,000 feet--and

a brief stay in December practically froze my toes off.

The Waucoba district certainly contains one of the greatest

Early Cambrian stratigraphic sections in all the world: the classic

Waucoba Spring section first described by C.D. Walcott in the

late 1800s. Except for development of the graded Waucoba-Saline

Road and a few additional minor off-road-vehicle trails, the

region likely appears much the same as it did in 1897 when Walcott

first passed through. The Precambrian-Early Cambrian transition

exposed here records the preserved remains of plants and animals

that lived in this part of what is now the Great Basin some 600

to 510 million years ago--a time so distant, so primordial that

it echoes back to a moment when the Spirit moved over the face

of the waters and said, "Let there be light."

|